Rev. Jesse L. Jackson: A Voice That Refused to Be Silenced

Civil rights leader, presidential candidate and founder of Operation PUSH leaves an indelible mark on American history The Rev. Jesse

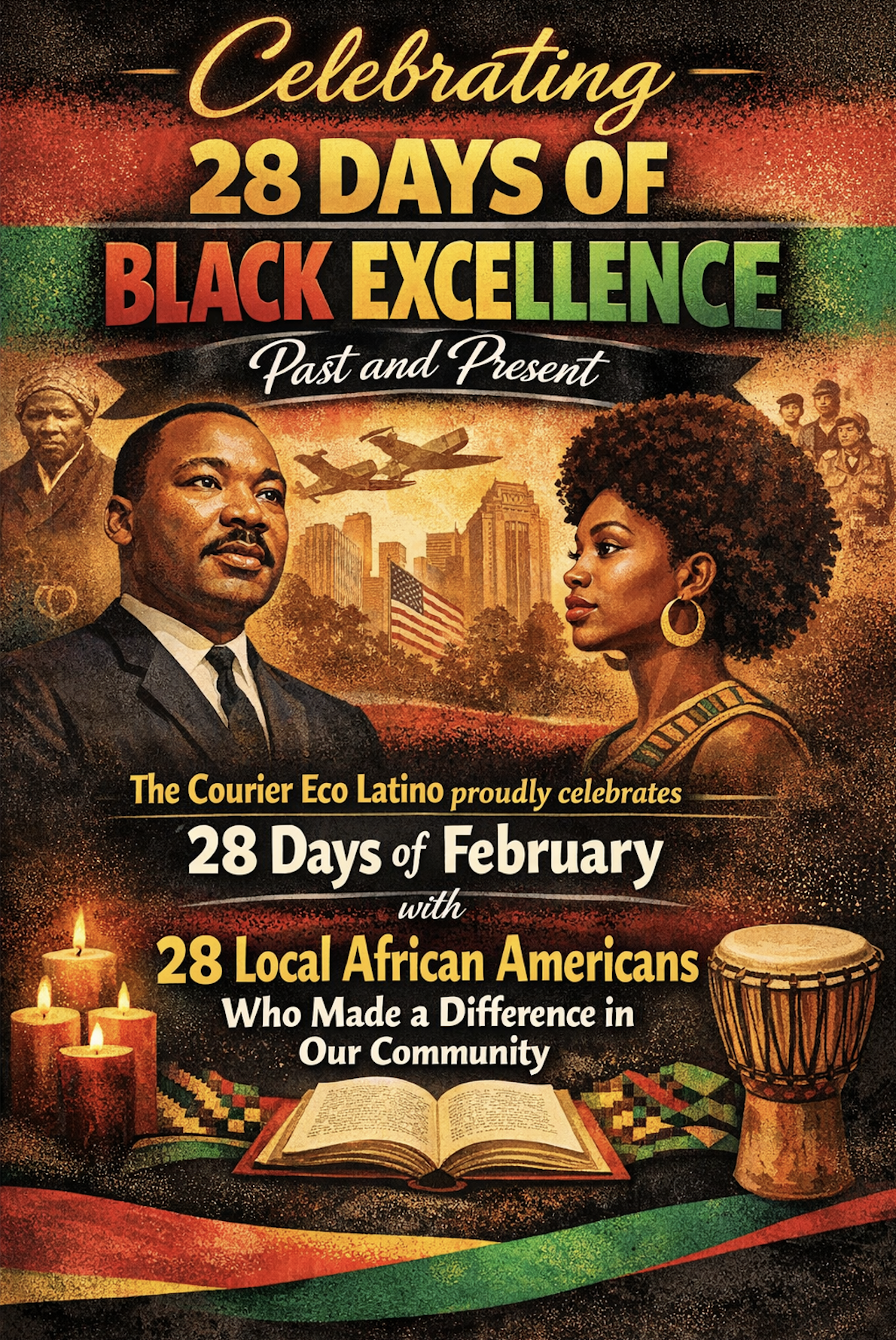

Throughout the month of February, The Courier Eco Latino honors Black History Month by spotlighting one local African American leader—past or present—each day. The series features trailblazers, educators, entrepreneurs, artists, advocates, and unsung heroes whose contributions have helped shape the soul, strength, and future of our community.

These are stories that may not always make headlines, but make a difference every day. From classrooms to boardrooms, from pulpits to protest lines, from small businesses to grassroots movements, each honoree reflects resilience, leadership, and service rooted right here at home.

Dr. M. Delmar Edwards, a pioneering surgeon whose steady leadership helped reshape the medical and civic landscape of Columbus, died Sept. 11, 2009. He was 82.

At his funeral service on Sept. 19, 2009, an ancient proverb was read that many said reflected his life: “Nothing in this world is as soft and yielding as water. Yet for dissolving the hard and inflexible, nothing can surpass it. The soft overcomes the hard; the gentle overcomes the rigid.”

Friends, colleagues and family members say Edwards embodied that principle — confronting racial inequities in medicine not with anger, but with dignity, patience and unwavering faith.

Born Dec. 19, 1926, in Fort Smith, Arkansas, Edwards was raised during the Great Depression by parents who instilled in him the values that would define his life. His father, Jesse Edwards, worked as a postal custodian, and his mother, Helen, a part-time housekeeper, infused their household with optimism and faith. As a boy, Edwards balanced schoolwork with tending the family cow — humble beginnings that belied a future of historic achievement.

Edwards attended Wilberforce University in Ohio before being inducted into the U.S. Navy. While serving as a young seaman, he developed a respiratory infection that led to hospitalization. A Navy surgeon took an interest in him, introducing him to surgical techniques and allowing him to assist in the operating room as a medical corpsman. The experience ignited a lifelong passion for medicine.

After his military service, Edwards returned to Wilberforce, later earning a degree from Morehouse College. He became the first Black male accepted to the University of Arkansas medical school. Following residency training in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where he met his wife of 49 years, Betty Margaret Redding, the couple settled in Columbus.

In Columbus, Edwards broke barriers as the city’s first Black surgeon. He rose to lead the General Surgery Section at the Medical Center and served as chairman of the Department of Surgery — positions rarely accessible to African American physicians of his era.

“He came at a time when African American physicians were not welcome,” said Dr. Sylvester McRae, a colleague Edwards recruited to Columbus in 1985. At that time, fewer than 10 Black physicians practiced locally. Today, there are dozens. McRae credited Edwards with recruiting many of them, earning him the moniker “Godfather of African American physicians.”

Beyond the operating room, Edwards was a civic force. He served as president of the Georgia State Medical Association and founded the Columbus-Fort Benning Medical Association, where he was president emeritus. He became the first African American member of the Columbus Rotary Club and served on the Columbus State University Foundation Board and the board of directors of AFLAC Inc.

His influence extended statewide and nationally. As a founding trustee of the Morehouse School of Medicine, Edwards provided both credibility and philanthropy during its formative years. A scholarship program bearing his name has supported generations of medical students.

“Dr. Delmar Edwards’ contributions in the early years of our institution were invaluable,” said Morehouse School of Medicine President John E. Maupin. Dr. Louis Sullivan, a founder and the school’s first president, said Edwards’ support was instrumental to the institution’s survival and success.

A man of deep faith, Edwards remained active in church and community affairs and quietly supported emerging leaders in law, politics and public service.

Colleagues say Edwards never lost sight of his purpose. Through integrity, optimism and steadfast faith, he carved a path through barriers that once seemed immovable — making the journey easier for those who followed.

In Columbus and beyond, the gentle force of his life continues to reshape the landscape he helped transform.