CEL News: Sunday Edition

Columbus State University Coach Robert Moore Sets Program Record with 160th Peach Belt Win READ MORE Reinvesting in Communities — A

History does not always repeat itself, but it has a rhythm. And if you listen closely in 2026, you can still hear an old tune playing in the background.

There is a pattern in American political history that rarely makes it into polite conversation but shows up cycle after cycle: when Black political independence begins to rise, forces invested in the status quo find creative ways to contain it. One of the most enduring strategies has been simple in design but sophisticated in execution — use a Black voice to challenge another Black voice.

Throw the rock. Hide the hand. It is not new. It is not accidental. And it is not isolated.

The Historical Blueprint After Reconstruction, when formerly enslaved people briefly gained political representation across the South, white supremacist power structures did not rely solely on open violence — though there was plenty of that. They also relied on political maneuvering. As Jim Crow hardened its grip, Black intermediaries were sometimes elevated, funded or amplified to legitimize policies that restricted Black advancement or to discredit leaders deemed too independent.

The strategy was elegant in its cruelty: make it look like internal disagreement rather than external suppression.

In the early 20th century, political boss systems perfected this method. In cities like Memphis under the machine of E.H. "Boss" Crump, Black community leaders were cultivated to deliver votes for white-approved candidates. Access was granted — but autonomy was not. The appearance of influence masked the absence of power.

Political scientists have sometimes referred to this as using a “messenger of meanness” — someone who looks like the community but carries a script written elsewhere. The goal was never empowerment. The goal was control.

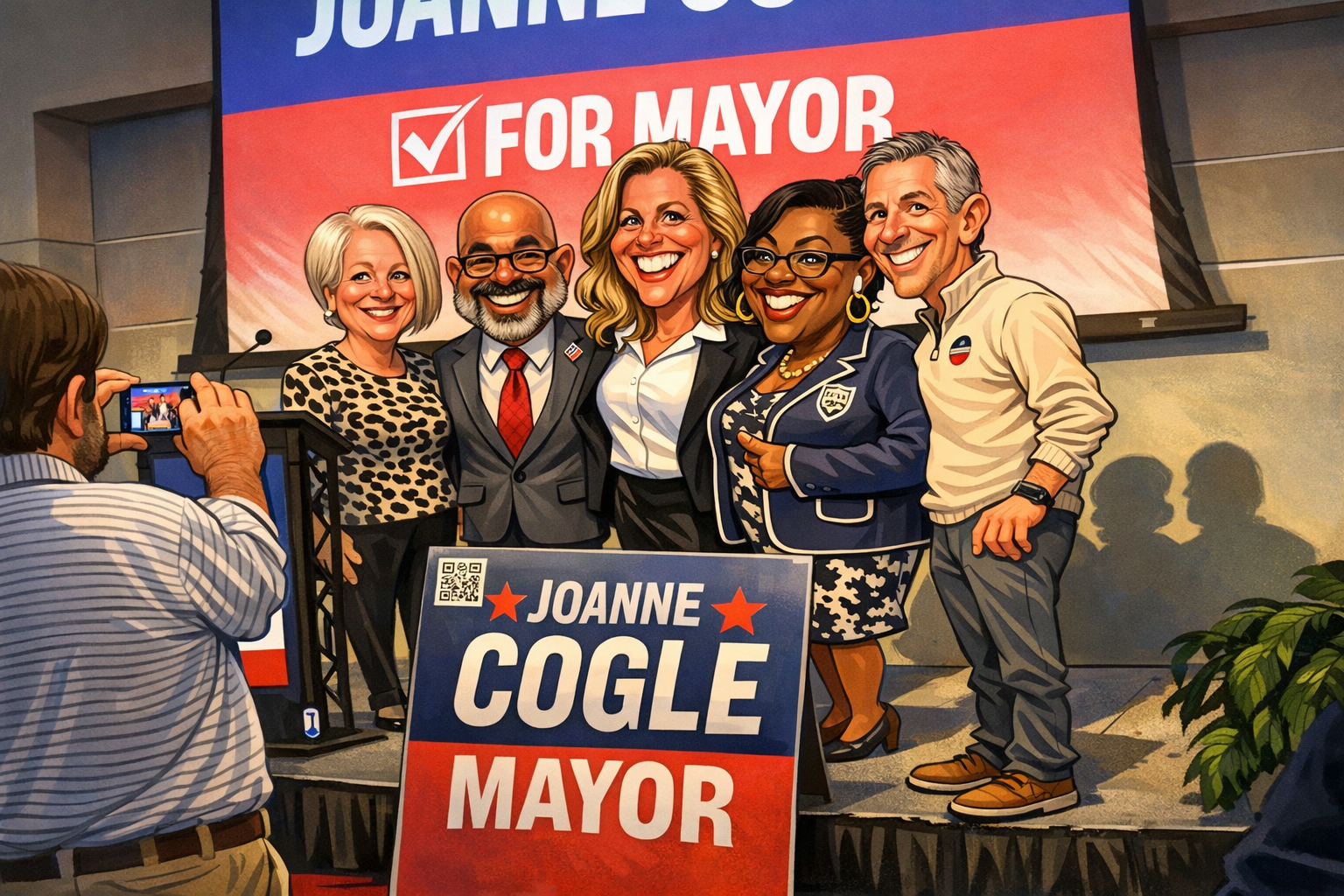

The Modern Upgrade Fast forward to 2026. The tactics have evolved, but the architecture remains intact. Today, instead of courthouse steps and smoke-filled rooms, the battlefield is digital. Campaign surrogates, social media influencers and targeted messaging often carry narratives that fracture Black political coalitions. White-led campaigns have learned that the most effective attack on a Black candidate is often delivered by another Black voice — especially on questions of authenticity, loyalty or ideological purity.

Research following the 2016 and 2020 election cycles documented targeted disinformation campaigns designed to appear as though they originated within Black activist spaces. Some messages encouraged Black voters to disengage. Others amplified fringe candidates to dilute consolidated support. The strategy was subtle: don’t attack from the outside — destabilize from within.

Even imagery has been weaponized. Scholars have documented instances in which campaign materials altered lighting and tone in ways that played to racial bias — a tactic so calculated it speaks volumes about the lengths political operatives will go to shape perception.

And then there is the “divide and conquer” primary strategy — amplify one Black candidate aligned with establishment interests to fracture support for another who is more independent or reform-minded. Provide funding. Provide visibility. Provide access. But always protect the larger structure. The method is old. The tools are modern.

Why It Works Three reasons.

Deniability.

When criticism comes from someone who looks like the target, accusations of racial motive become easier to dismiss. “This isn’t about race,” they say. “It’s just politics.”

Narrative Control.

If you can frame the conflict as an internal dispute, you remove scrutiny from the larger power dynamic shaping it.

Status Quo Protection.

Independent Black political power — power that does not require validation or permission — has always been viewed as destabilizing to entrenched systems.

So the system adapts.

A Word of Caution — and Clarity Let’s be clear: disagreement within the Black community is not only natural; it is necessary. We are not a monolith. Debate sharpens policy. Competition clarifies vision. But there is a difference between organic disagreement and engineered division.

History teaches us to ask hard questions:

From the pew where I sit, the lesson of 2026 is not that nothing has changed — it’s that power has learned how to change its clothes. The language is softer. The platforms are digital. The operatives are more polished.

But the objective remains familiar. And here is the deeper truth: strategies only work when communities forget their history. Reconstruction. Jim Crow. Political machines. Targeted messaging. Divide and conquer. We have seen this before. The question is not whether the tactic exists. The question is whether we recognize it when it arrives dressed as “help,” “strategy,” or “support.”

History whispers. Wisdom listens. And if we are honest, in 2026, the whisper sounds awfully familiar.