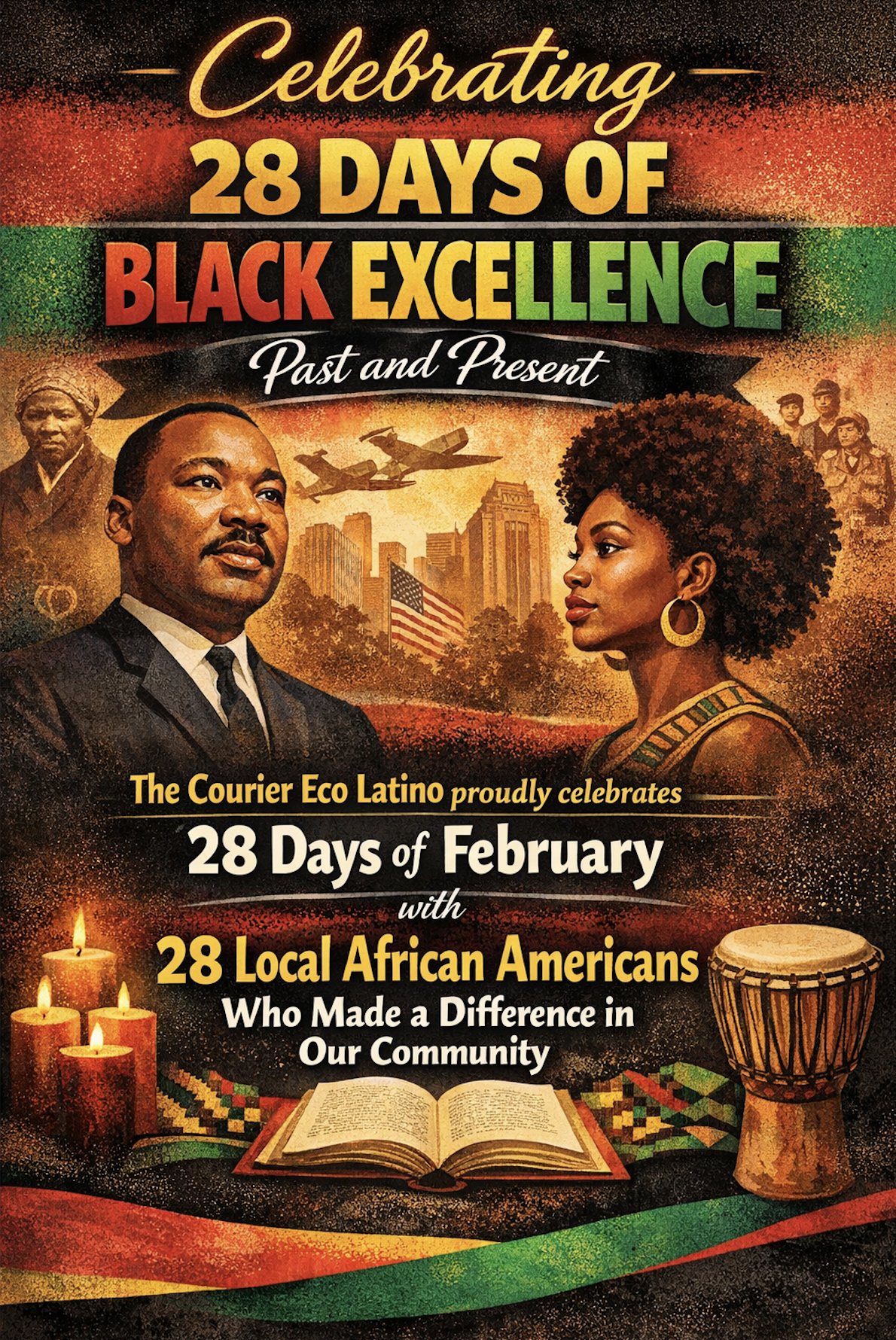

Celebrating 28 Days of Black Excellence. Past and Present: Primus E. King

Throughout the month of February, The Courier Eco Latino honors Black History Month by spotlighting one local African American leaderor

Throughout the month of February, The Courier Eco Latino honors Black History Month by spotlighting one local African American leaderor organization—past or present—each day. The series features trailblazers, educators, entrepreneurs, artists, advocates, and unsung heroes whose contributions have helped shape the soul, strength, and future of our community.

These are stories that may not always make headlines, but make a difference every day. From classrooms to boardrooms, from pulpits to protest lines, from small businesses to grassroots movements, each honoree reflects resilience, leadership, and service rooted right here at home.

On the morning of July 4, 1944, Primus E. King walked into the Muscogee County Courthouse determined to do what he was legally entitled to do: vote.

Instead, the African American Columbus resident was forcibly escorted from the building by a law officer and denied a ballot in Georgia’s Democratic primary — the only election that effectively determined state and local leadership in the one-party South.

King’s rejection was not spontaneous. It was part of a carefully planned legal challenge organized by a group of Black civic leaders led by Dr. Thomas H. Brewer. After being turned away, King walked several blocks to the office of white attorney Oscar D. Smith Sr., who immediately filed suit against members of the Muscogee County Democratic Party Executive Committee, chaired by Joseph E. Chapman.

The case, King v. Chapman, became a pivotal legal battle against Georgia’s white primary system, which barred Black citizens from participating in Democratic primaries under the claim that the party was a private organization.

Arguments began in federal district court in Macon in September 1945. King’s attorneys, Smith and Harry S. Strozier of Macon, argued that the denial of King’s vote violated the Fourteenth, Fifteenth and Seventeenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. They sought $5,000 in damages.

On Oct. 12, 1945, U.S. District Judge T. Hoyt Davis ruled in King’s favor, awarding him $100 plus 7 percent interest — a symbolic sum that signaled a major constitutional victory. The defense appealed.

On March 6, 1946, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans upheld the lower court’s ruling. Judge Samuel H. Sibley wrote that Georgia’s election laws sufficiently connected the state to the Democratic primary, meaning the state had effectively “put its power behind the rules of the party.”

Serving as amicus curiae for King was Thurgood Marshall, then a rising NAACP attorney who would later argue Brown v. Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case on April 1, 1946, the ruling stood — effectively ending the white primary in Georgia. Combined with the state’s earlier abolition of the poll tax in 1945, the decision dismantled key barriers that had blocked Black Georgians from meaningful participation in elections.

More than $10,000 was raised by the Columbus chapter of the NAACP and local supporters to fund the nearly two-year legal fight.

King was not a career activist. Born Feb. 5, 1900, near Hatchechubbee, Alabama, to sharecroppers Lucy and Ed King, he never received formal education. As a boy, he moved with his family to Columbus, where he helped build the Meritas cotton mill.

In 1921, he married Genie Mae King, a longtime public school teacher. The couple had one daughter.

King worked as a chauffeur and butler for a prominent white family and endured the humiliations common to Black workers in the segregated South. He later became a self-taught barber, saving enough money to purchase his own shop in pursuit of economic independence.

In 1939, after a religious conversion, King became pastor of Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church and later ministered at Salem Baptist Church. His faith, he would say, fortified him during the legal struggle, especially as he faced threats against his life.

Though his name appeared in newspapers nationwide during the lawsuit, King returned to a quiet life of barbering and ministry. He sold his barbershop and retired in 1963.

In time, the political establishment that once barred him would honor him.

In 1973, Columbus Mayor Bob Hydrick proclaimed June 28 as Primus E. King Day. In 1977, the Muscogee County Democratic Executive Committee paid King the $100 judgment plus accumulated interest — totaling $324.70. In 2000, Gov. Roy Barnes signed legislation naming a stretch of highway in Columbus the Primus King Highway.

King died Nov. 3, 1986, in Columbus.

His act of defiance on Independence Day 1944 helped secure voting rights for thousands of Black Georgians who followed. Though he did not seek prominence, Primus E. King’s courage placed him firmly in the lineage of ordinary citizens whose quiet resolve reshaped American democracy.